You have to tread carefully when it comes to terminating at-will employees. You may think you have just cause to fire a badly performing team member, but if there appear to be exceptions or the at-will employee files a lawsuit, you could face large fines and penalties.

So, keeping up to date with at-will laws is essential. Different states honor different exceptions, so it’s important to be aware of what you could get in trouble for depending on where your business is located.

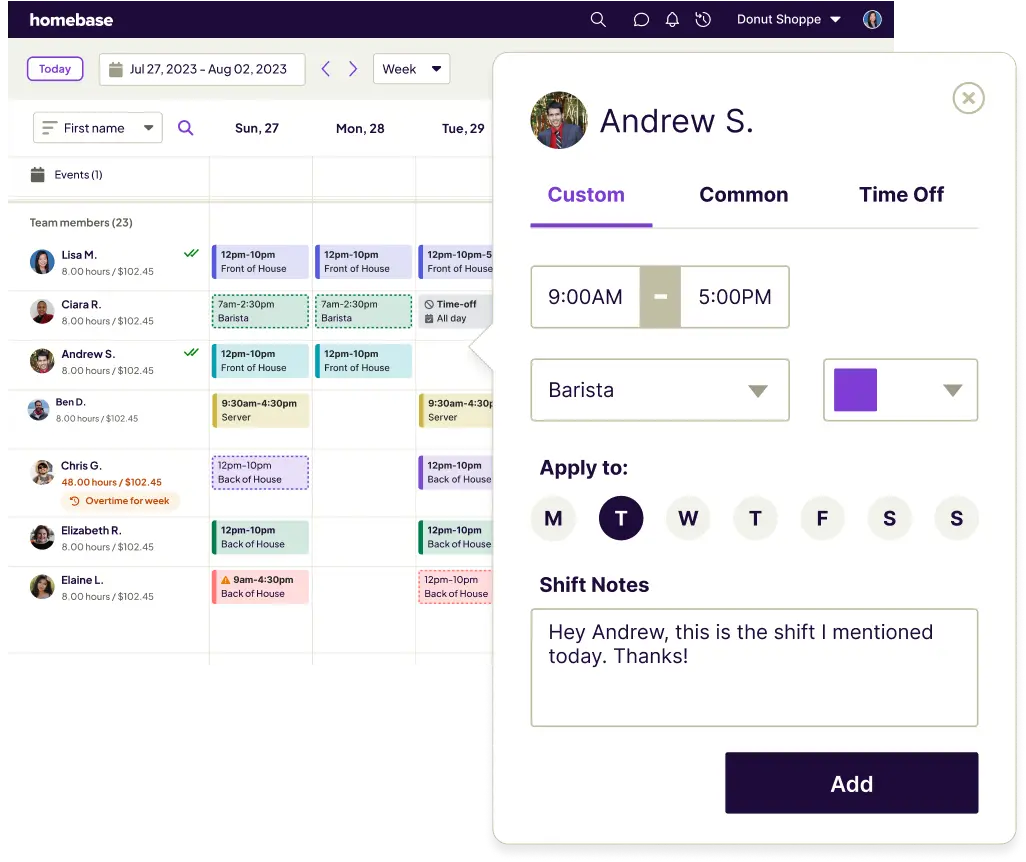

Read our guide to find out what rights you have as an at-will employer and all the possible exceptions that could apply to your business. We’ll also show you how Homebase’s HR Pro tool can guide you through terminations with minimal risk to your business.

What is At-Will Employment?

At-will employment refers to employers’ legal right to terminate employees for any reason outside of federal and state law protections. And every state except Montana has “at-will employment.” Basically, this law means employers don’t have to state a reason for terminating a staff member or give notice.

But many states have exceptions to this rule, meaning an at-will employment relationship doesn’t let you terminate your staff for absolutely any reason. If an exception applies to your employee, you have to prove you fired them with good cause. And violating these exceptions can be considered wrongful discharge based on your location and could lead to your employee filing a lawsuit against you.

Disclaimer: The following information is intended as a guide, not legal advice. If you’re planning to hire at-will employees or terminate one or more of your staff members, contact your state Department of Labor (DOL) office or an employment attorney, or consider reaching out to one of Homebase’s very own HR professionals.

Federal Exceptions to At-Will Employment

To protect yourself and make sure you’re doing right by your team, it’s best to know the circumstances when you can’t terminate at-will employees. Federal law states two main exceptions to at-will employment, which are discrimination and retaliation. Let’s break down exactly what that means for you.

Discrimination

There are federal laws, as well as additional state legislation, against firing someone for discriminatory reasons. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), you may not fire an employee based on the following:

- Race

- Color

- Religion

- Sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, or gender identity)

- National origin

- Age (40 or older)

- Disability

- Genetic information (including family medical history)

Retaliation

If one of your staff members reports discrimination, you can’t fire them in revenge, according to federal labor law. In fact, you can’t treat them any differently than you did before, or you may face fines. The EEOC says you can’t retaliate against an employee for the following reasons:

- Filing or being a witness in a complaint, charge, investigation, or lawsuit

- Communicating a case of discrimination or harassment to a supervisor

- Answering questions as part of a harassment investigation

- Refusing to follow orders that result in discrimination

- Resisting sexual advances or intervening to protect others

- Requesting disability or religious accommodation

- Attempting to uncover potentially discriminatory wages

State Exceptions to At-Will Employment

Many states have their own exceptions to at-will employment — although some have none at all. Three of the most common are:

- Firing employees for following public policy

- Implied contract

- Acting in bad faith

We’ll go into each exception in more detail below and list the states that don’t allow them.

Public Policy

You can’t terminate employees for either:

- Doing something that complies with federal or state laws, or

- Refusing to do something that breaks a law

This is called ‘wrongful dismissal’ and may be a violation of employee rights.

For example, if an employee suffers an injury on the job and files a workers’ compensation claim, you can’t fire them for doing so. And if the staff member doesn’t want to engage in an illegal activity that you request, you can’t terminate them for that reason either.

And if an employee can prove the termination violates the public policy exception, they may be entitled to:

- Compensatory damages. The business may have to pay them back for lost income, lost benefits, and/or lost future earnings.

- Punitive damages. If a business’s actions are particularly harmful to the employee, they’ll get extra payments.

- Attorney fees. The employer may have to pay the employee’s litigation and attorney fees.

An example of a business violating the public policy exception

In the case of Fleshner vs. Pepose Vision, a Missouri ophthalmologist fired an at-will employee after she answered a federal investigator’s questions about their overtime practices. Assisting the federal government is public policy. As Missouri honors this exception and the employee could prove she was wrongfully terminated, the business had to pay $125,000 in compensatory and punitive damages.

States that don’t honor the public policy exception

This is the most popular exception, but the following states don’t honor it:

- Alabama

- Florida

- Georgia

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Nebraska

- New York

- Rhode Island

Implied Contract

Many states recognize an implied contract exception to at-will employment. That means you can’t fire a staff member when your words, actions, or business practices indicate any kind of job security or alternative termination process. Even if you don’t explicitly promise an employee anything verbally or in writing, the implied contract exception still applies.

For instance, if you offer an employee more senior responsibilities and then fire them, they could claim wrongful termination. You may never have offered them a senior position, but the act of delegating these tasks to them implies a potential promotion and a future with your business.

Or, you might have included a list of reasons for termination in your employee handbook. If you turn around and fire a team member for a reason you didn’t mention there, they could claim wrongful termination.

If an employee can prove wrongful termination because you broke an implied contract, you’ll probably owe expectation damages. That means paying them what they would have received under the implied contract.

An example of a business violating the implied contract policy

In Elizabeth Stewart vs. Cendant Mobility Services, a Connecticut business promised an employee that her job was safe after firing her husband. But when he took a job with a rival business, they reduced her hours and eventually fired her. She sued Cendant Mobility Services for breach of implied contract, and the court awarded her $850,000.

States that don’t honor the implied contract exception

The states that don’t allow this exception include:

- Alabama

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Indiana

- Louisiana

- Massachusetts

- Missouri

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- Texas

- Virginia

Good Faith

Some states also recognize the “implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing” exception. In other words, you must have a “just cause” for firing an employee that isn’t for dishonest or selfish reasons.

Good faith violations could include making up a reason to fire an employee because you want to hire cheaper labor or because you don’t want to offer them benefits they’re entitled to.

If you fire someone for unjust reasons or break your own policies, an employee can file a wrongful termination claim against you. Courts tend to look at the following to justify these kinds of claims:

- Whether or not you followed your employee handbook

- How long the employee worked for you

- Whether or not you critiqued their performance over time

- General notions of fairness

An example of a good-faith lawsuit

There aren’t many examples of successful good-faith lawsuits against businesses. But it’s still in your best interest to check whether you’re in one of the states that honor this exception to avoid legal action. Because even if a lawsuit is unsuccessful, it can still cause stress, waste time and money, and tarnish your business’s reputation.

In the case of Vander Veur vs. Groove, a Utah business promised to give employees a commission on every TV installation they completed. One staff member had contracted but not finished 30 installations when he was fired, making him ineligible for the extra payment. Later, he filed a lawsuit claiming the business had violated the covenant of good faith.

Although the lower court supported his claim, the Supreme Court didn’t. This was because Groove had explicitly written in the contract that employees must complete installations to receive a commission. However, the story became controversial, made news headlines, and generated a lot of bad press for the business.

States that DO honor the good faith exception

As only 16 states follow this exception, we’ll list those instead for simplicity. They are:

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- California

- Delaware

- Idaho

- Indiana

- Massachusetts

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- South Carolina

- Vermont

- Utah

- Wyoming

Rights of an At-Will Employee

We’ve discussed employer’s rights, but what about at-will employees? Here’s what staff with an at-will status can do:

- Quit without advance notice or explanation

- Practice their religious beliefs without interference from their work

- Take time off for medical reasons, including disability and pregnancy

- Take time off for purposes protected by law, like jury duty and voting

- Be treated equally to other staff members regardless of race, religion, gender, age, national origin, or pregnancy status

- Expect their employer to follow their established termination policies — for example, what’s written in the employee handbook

- Comply with state and federal law without fear of retaliation

But at-will employees can’t:

- Refuse to agree to the contract terms — at-will employment is the default

- Insist on an explanation for dismissal in states that don’t honor the ‘just cause’ exception

Challenges of At-Will Employment

Hiring at-will employees might seem like an attractive option. It simplifies the termination process and gives you more freedom over who’s on your team. But there are plenty of setbacks that may make at-will employment less appealing to you.

- At-will employment laws are intricate: As we’ve seen, states follow different exceptions that can change at any time. They also might interpret certain exceptions differently. To avoid wrongful termination claims, you may need guidance from an expert HR professional.

- Neither you nor your employees have security: That means your staff members may not feel like they can make long-term plans around their jobs and you risk having to deal with sudden staffing shortages.

- You may face unfair wrongful termination claims: If you fire an employee with just cause but they appear to fall under an exception, you can still face penalties. For example, you could terminate an older employee who’s consistently underperforming and they could perceive your dismissal as age discrimination.

- Your business may have difficulty attracting employees: Most employees want job security. If you don’t provide it but your competitors do, you may miss out on the best candidates.

- Staff relationships may suffer: When employees feel insecure about their jobs, they’ll be less likely to come to the business’s owner or manager for support. But it’s not good to make employees feel isolated and let resentment build up.

- Problems are less likely to get solved: Employees may not report problems or complaints when they’re worried about getting blamed or even fired for them. But it’s important for team members to report all issues that come up as they come with valuable insights and improvement opportunities that help you better your business.

How Contract Modifications Can Nullify At-Will Employment

If a work contract states a specific time for employment or suggests just causes for termination, the at-will status no longer applies. However, businesses typically only draw these kinds of contracts up for high-level employees.

As a small business owner, you’re more likely to encounter a collective bargaining agreement (CBA). A CBA is a contract that a union and employer negotiate regarding wages, hours, and terms and conditions of employment. These contracts typically include a clause that says you can only fire employees for just cause.

To learn more about when you can fire employees with a contract, check out our article on what counts as just cause for termination and what doesn’t.

How Does At-Will Employment Compare to Other Employment Types

At-Will Employment vs Employment Under Contract

At-will employment differs significantly from employment under contract. The absence of a written agreement in at-will employment offers greater flexibility for the employer. Conversely, contract employment outlines specific terms such as wages, benefits, and conditions for termination, offering more stability for the employee.

At-Will Employment and Job Security

In terms of job security, at-will employment offers less stability than other types. The employer or the employee can terminate the working relationship at any moment without repercussions. This is in stark contrast to employment under contract, which usually involves terms that must be met before termination.

At-Will Employment and Compensation

When it comes to compensation and benefits, at-will employment also lacks the assurances provided by contract employment. Employers can alter benefits and wages without any requirement for notice. In employment under contract, these terms are fixed in a written agreement.

At-Will Employment and Right-to-Work Employment

Right-to-work employment mainly addresses union membership and doesn’t influence job security, compensation, or termination processes. When comparing at-will employment to right-to-work employment, it’s clear that the latter is less about individual employment terms and more about collective bargaining rights.

At-Will Employment and Employee Rights

Finally, at-will employment provides fewer protections to workers than other employment types. The power to terminate the employment relationship rests heavily with the employer, while in contrast, employment under contract and right-to-work laws can offer additional rights and protections related to union membership.

Have More Questions About Termination and At-Will Employment?

Small business owners and managers generally aren’t deeply familiar with employment law. That’s hardly your fault — you need to prioritize running your business and getting through your ever-growing to-do list.

Protecting your business and the rest of your staff from wrongful termination suits is essential. But how can you do that without hiring an HR manager that you don’t have the budget for?

Homebase can help. With HR Pro, you’ll get access to certified HR experts who can answer any questions about specific employee situations, review your existing termination policies, and even help you create new ones. And our affordable plans mean Homebase can be your HR manager without the same high cost.

At-Will Employment FAQs

What is the difference between at-will and contract employment?

The main difference between at-will and contract employment is that either the employer or the employee can terminate an at-will working relationship at any time without just cause.

By comparison, employers must have a compelling reason to fire employees with a contract. Contracted employees are also usually required to work a notice period before they leave their jobs.

Which US states are at-will employment?

Every US state has at-will employment except for Montana. Employers in Montana must always provide just cause for termination. However, Montana does have a 12-month probationary period for new employees where they can be fired without explanation.

Share post on

Shelbie Watts

Shelbie Watts is the Content Marketing Manager for Homebase. She works to provide relevant, informative and engaging material to both local business owners and their employees, and hopes to make work easier one blog at a time.

Remember: This is not legal advice. If you have questions about your particular situation, please consult a lawyer, CPA, or other appropriate professional advisor or agency.

Popular Topics

Homebase is the everything app for hourly teams, with employee scheduling, time clocks, payroll, team communication, and HR. 100,000+ small (but mighty) businesses rely on Homebase to make work radically easy and superpower their teams.